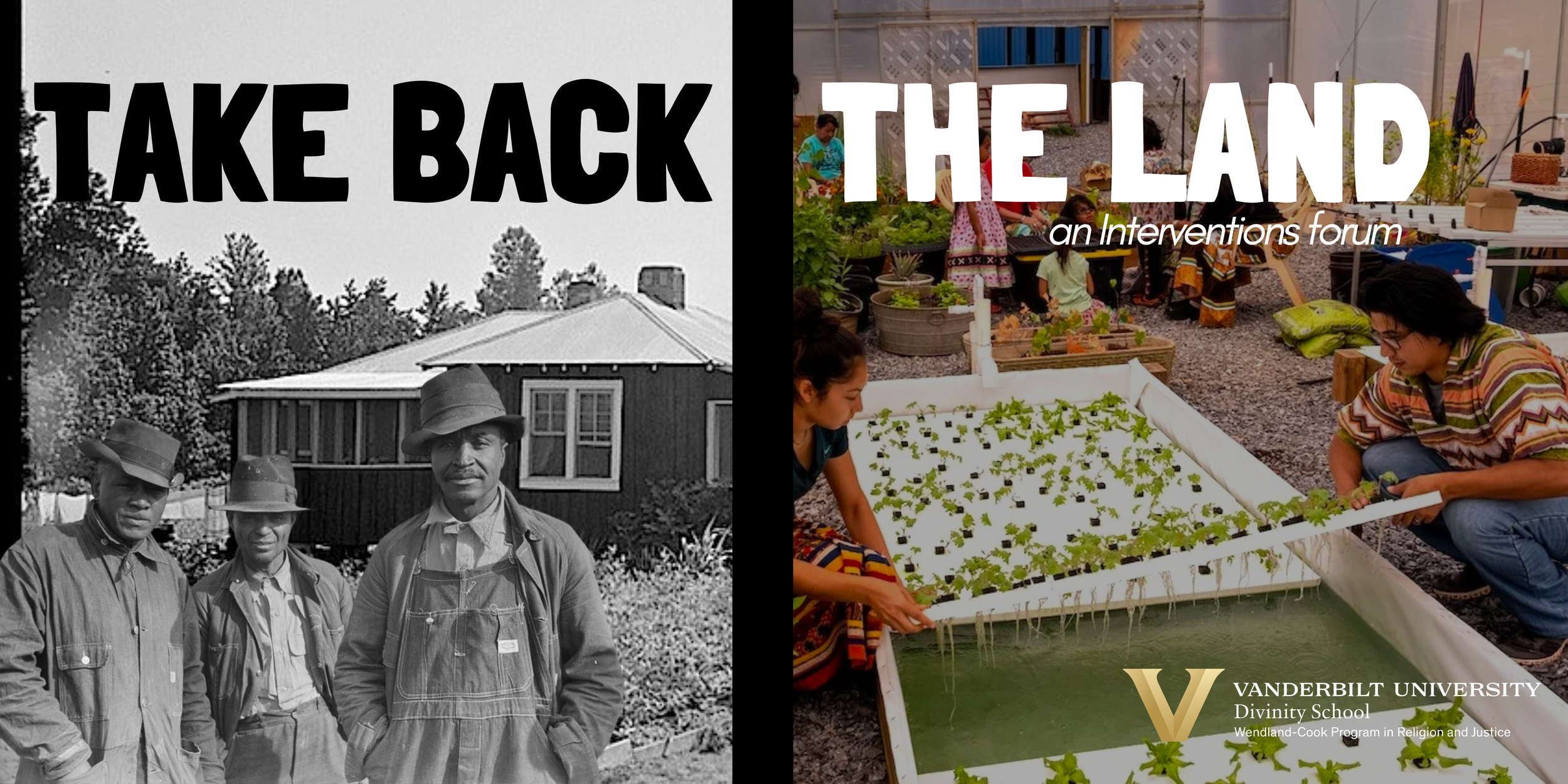

Take back the land

As part of the Vanderbilt University Sesquicentennial celebration, last fall the Wendland-Cook Program was awarded a Sesquicentennial grant for our project, “The Unexplored Legacy of the Social Gospel Movement in the South: The Vanderbilt Contribution.” This Interventions forum is the second in a series of three on this subject. To read the first forum introducing the topic and series, read here: The Social Gospel Movement in the South.

This forum focuses on the distinct story of Rochdale and Delta Cooperative Farms (later named Providence Farms) in Mississippi, founded by social gospel movement leaders in the 1930s and 40s. The distinct political and economic vision here was inspired by cooperative economics and political democracy. The uniqueness of this project was its focus on cooperatives as a way to build economic power against racial and plantation capitalism in the south.

The forum will also explore how cooperative agriculture is an urgent and viable way forward to build economic and political power today against racial and economic injustices.

Contributors: Joerg Rieger, Dan Rhodes, and Ed Whitfield

Land and Labor, Planet and People

Joerg Rieger

9 November 2023

Land and labor, the planet and people belong together. This is a fundamental claim that might be considered at the heart of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the so-called Abrahamic traditions. The connection of land and labor starts with the creation stories, where God plants and humans tend a garden, putting together divine, human, and other-than-human labor for the flourishing of life (Genesis 2:8 and 2:15). Unfortunately, much of this wisdom has been suppressed in each generation for thousands of years. Especially in many Christian traditions, the gaze of the faithful has too often been turned away from the ground, from people, and from this world, towards the sky and to other worlds.

Still, in every generation, some faith traditions have sought to reclaim and rebuild connections with land and labor. In the United States, in early 1865, twenty African American religious leaders, nineteen of which had been enslaved, put land and labor together in a conversation with General William Tecumseh Sherman. This is the background of Sherman’s famous campaign for “forty acres and a mule” for formerly enslaved African Americans, which was abandoned again quickly by Andrew Johnson, the president succeeding Abraham Lincoln. At the heart of the conversation, which was first brought to my attention by worker cooperative developer Ed Whitfield (now published in “What Must We Do to Be Free?” Prabuddha: Journal of Social Equity [2018] 2:45-48), was human agency—the ability of people to do creative work and to benefit from this work. Such agency, of course, was denied under the conditions of slavery in the United States. Unfortunately, the ability to work and to benefit from one’s work is still severely limited under the conditions of neoliberal capitalism, where the work of people and the planet is generally exploited for the production of profit for the few rather than the many. This is made worse by the exigencies of class, race, and gender, which are still actively employed in preventing land and labor, people and planet, from fully flourishing.

While the enslavement of others is the most extreme form of exploitation imaginable, exploitation continued in various forms after slavery was officially abandoned in the United States. Garrison Frazier, an ordained Baptist minister and the spokesperson of the twenty African American religious leaders, presented the problems and the solutions to Sherman in this way: “Slavery is, receiving by irresistible power the work of another man, and not by his consent (emphasis in original). The freedom, as I understand it, promised by the [Emancipation P]roclamation, is taking us from under the yoke of bondage, and placing us where we could reap the fruit of our own labor, take care of ourselves and assist the Government in maintaining our freedom.” It is worth noting that this concern for the ability to labor and to have agency underlies the demand for land, which today is frequently made without reference to labor: “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor–that is, by the labor of the women and children and old men; and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare” (“Newspaper Account of a Meeting between Black Religious Leaders and Union Military Authorities,” Freedmen and Southern Society Project, June 2021, http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/savmtg.htm).

Having experienced the horrors of enslavement in their own bodies, and therefore the total dispossession not only of land but also of labor and agency, the sense of these religious leaders that land and labor are connected in moving beyond slavery is crucial. This connection is still as relevant today as it was then. Similar sentiments are also expressed in Native American struggles in the United States, where labor and community wealth also shape the indigenous concerns for land, putting together human and nonhuman productive and reproductive labor (Kari Marie Norgaard, Ron Reed, and Carolina Van Horn, “Continuing Legacy: Institutional Racism, Hunger, and Nutritional Justice on the Klamath,” in Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability, ed. Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman [Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011], 25. See also Joerg Rieger, Theology in the Capitalocene: Ecology, Identity, Class, and Solidarity [Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2022], chapters 1 and 2).

Building on these fundamental insights, one of the most powerful connections of land and labor can be seen in cooperative agricultural enterprises. The history of the Delta and Providence Farms in Mississippi exemplifies what is at stake (see Jerry W. Dallas, “The Delta and Providence Farms: A Mississippi Experiment in Cooperative Farming and Racial Cooperation,” Mississippi Quarterly 40:3 [Summer 1987]: 283-308). In their 20 years of existence, starting in 1936, these farms established farming cooperatives for agricultural workers in the Mississippi Delta. In these enterprises, land was the foundation for building the power of one of the most impoverished groups in the United States through their labor—groups which consisted of both Black and white workers. With leadership rooted in the community and an elected board that was required to be racially diverse, in these cooperative enterprises economic democracy became the foundation of political, cultural, and even religious democracy. As a result, the realities of class exploitation and racism were addressed together, creating seemingly impossible spaces and opportunities in the heavily segregated South of the United States.

Located in the state of Mississippi, it is no wonder that Delta and Providence Farms received pushback, and it was pushback against their resistance to racism that eventually forced them to close their doors in the 1950s. Yet it was the connection of land and labor, people and planet, which first provided space for alternative ways of life. Since Black and white workers had worked side by side in the cotton fields for years, collaboration at work was less controversial than racial equality. In the Delta and Providence farms, it was precisely this economic collaboration that became the foundation for solidarity across the artificially drawn lines of race. And while the cooperatives were never completely able to overcome these lines—reinforced by Mississippi state law and its constant threat to shut everything down—examples of resistance to racism included white families successfully pushing for the same educational opportunities for Black families, whose children received substantially less education in Mississippi. As a result, the farming cooperatives were able to provide Black schoolchildren an additional four months of schooling each year, putting them on par with white schoolchildren.

Despite the eventual shuttering of promising projects such as Delta and Providence Farms, the work continues. This is why the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice at Vanderbilt is collaborating closely with worker cooperatives and related efforts to build economic democracies that put together land and labor, people and planet. Such is the goal of our Solidarity Circles, which connect faith communities and solidarity economy enterprises in mutually generative relationships.

Joerg Rieger is the Distinguished Professor of Theology, Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies at Vanderbilt Divinity School and Graduate Department of Religion, Affiliate Faculty, Turner Family Center for Social Ventures, Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University, and the Founder and Director of the Wendland-Cook Program.

Theological Geography: The Black Mountain School of Theology & Community and Re-Learning Out of the Space of Racial Capitalism

By Daniel P. Rhodes

9 November 2023

“The question of how one should imagine space,” theologian Willie Jennings claims, “is by far one of the most complex questions facing the world today” (Jennings, Christian Imagination, 250). It is also a question of utmost concern for the church, for the way we imagine space informs how we inhabit it. Yet, for many churches and for many Christians, little attention has been given to the spatial dimension of their existence, rarely, if at all, garnering theological analysis. Theology has been thought to stand over and above physical location, untouched and uninformed by it in its universal themes and teachings. As Jennings puts it, such a “diseased social imagination,” however, has had substantial ramifications because it, in fact, has never really been disconnected from the vision, configuration, and organization of the land and its people, animals, plants and trees, waterways, etc. (Jennings, Christian Imagination, 6). The reality underneath such a docetic theology has been the operation of the forces of racial capitalism bent on a segregationist agenda that extracts and exploits those relegated to the periphery for the accumulation, benefit, and profits of those deemed to reside at its core. Hence, the project of whiteness as a racial capitalist regime has continually proclaimed its own gospel of improvement, development, civilization, domestication, and increased productivity, a message many churches have too easily bought and accepted. Paying no attention to the land and to the spatial movements of intimacy relayed in Scripture and manifest in the Incarnation, too many of our churches have become glimmering temples to the advance of this malformed mentality.

We have heard it said that the market has winners and losers. But what we don’t always hear is that the market requires losers, and not just in payouts and investments. The market demands losers in labor, land, and natural resources by dividing out those sites and peoples that can be expropriated and those that do the expropriation. That is, it generates a core and a periphery wherein that periphery (or a margin)—its people, land, and resources—are forced into service of the core. The system then replicates this division across its entire expanse, structurally establishing a system of extraction. Segregated accordingly, those outside the core are rendered useable, those in the core believing they were created to own and dominate creation. Like with Rome, whose imperial rule put the bodies and lands of those they conquered to work for the aristocracy, so capitalism’s own version of this colonial project has spread across our globe, shaping and organizing space along these coordinates of core and periphery. Through displacement and subjection, those forced to work the land are not those that own it, just as those that own and manage our global companies are not those that toil in them for minimum wage. Empire imposes such segregations because this is the way it sees space itself, coercing all in those places it reigns into assimilation.

But the true good news is that we do not have to remain this way. Nor do we have to remain committed to its imperatives of segregation, division, extraction, and exploitation. A renewed theological consideration of geography is a critical practice for leading us out of our worship of racial capitalism and its world-shaping and town-shaping powers. Indeed, if we allow ourselves to read experiments like Providence Farms from a theological perspective, then one thing they may teach us is not only how the production and cultivation of food relate to how we care for the environment (on some global level) but also, and maybe more importantly, how a farming cooperative might embody in its intimate joining of people, land, and agriculture a deep resistance to the dispossession, extraction, and oppression that suffuse racial capitalism and its waves of creative destruction. By connecting the economic, social, political, and religious, and suffering no abstraction of the latter from the others, cooperatives like Providence Farms begin to stake out an alternative—something our churches desperately need to learn to be if they are not to simply recede into an oblivion of insignificance and irrelevance. This is what made Providence Farms, for all of its faults and challenges, not just a racial experiment, but a political, economic, and ethical one too.

Building on this social gospel legacy, one of the most important things we teach congregations at the Black Mountain School is to begin to study and attend to their location—training them to begin to orient themselves to their towns and cities, villages and neighborhoods through a theological geography. A big part of this is because the fight for social justice and the social dimension of the gospel in the South has never been far from the land. Whether it was the plantation, the mining company, the mill factory, or now the bank’s financing of real estate, the struggle for the limits to private property remains at the center of this struggle because the core principle of the empire of capitalism is the limitless power of such. Coercive and violent to its core, the regime lives by segregations between the propertied and those that are made property. Hence, it detests and resists cooperative joinings and solidarities like Providence Farms. Building on the radical legacy of the social gospelers who glimpsed the need to live with one another and with the land differently, the Black Mountain School seeks to teach and train congregations, organizers, and activists to read their geography both to see the extent of the segregations upon which they reside while also attending to the sites where new joinings of collaboration and cooperation can embark on altering the landscape (Jennings, Christian Imagination, 113).

Education played a key role in promoting the Social Gospel, especially in the more radical initiatives like Providence Farms. Vanderbilt Divinity was instrumental in indirectly fostering such initiatives, as figures like Sherwood Eddy who helped found the farm were formed and catalyzed there. That legacy extends too to figures such as Don West and Howard Kester among others. It is within this legacy of radical education and transformation that the Black Mountain School seeks to root our own work as an institution of public theological education helping congregations and communities to shake off the confines and familiarity of racial capitalism and re-envision and re-position themselves on the land ordered to joining and connecting rather than owning, dividing, and extracting.

Dan Rhodes is Associate Professor of Contextual Education at Loyola University Chicago’s Institute of Pastoral studies. He has developed innovative programs in theological education grounded in theological action research. Prior to Loyola, he served in ministry for 9 years and has extensive experience as a leader in community organizing. He is one of the founders of the Black Mountain School of Theology and Community.

The Slow Process of Community Discernment:The Delta Commons

An interview with Ed Whitfield by Aaron Stauffer

1 December 2023

The Delta Commons Group is a collaborative that promotes and facilitates the development of opportunities for Clarksdale, Mississippi residents and others throughout the Delta region of Mississippi and Arkansas. DCG works to offer affordable high-quality places to live, work, in order to preserve and enjoy the rich heritage of the region. The Delta Commons Group includes artists, cultural workers, policymakers, advocates, developers, and organizers who collectively engage in building and maintaining an inclusive local economy rooted in productive and sustainable community ownership. Ed Whitfield, a longtime friend of the Wendland-Cook Program and the Southeast Center for Cooperative Development is on the board of the DCG and spoke with Associate Director, Aaron Stauffer about the DCG and it’s strategy of leadership development and cultural organizing in the south, especially considering the legacy of the Delta and Providence Cooperatives.

EW: The Delta Commons group came together in late 2020. In early 2021, we got incorporated. There was an old hospital here that had been a segregated white hospital and it had been abandoned in the 1970s, probably, when they built the Delta Regional Medical Center, a larger hospital that was more modern. And the family that bought our current building was one of the practicing physicians at the new hospital. And he put his medical offices in it for a while and operated it there until he passed away. Then his family had it and you know, for them it became mainly a tax burden, and they were looking to do something with it, but wanting to do something useful with it. So I ended up hearing about that from some people here locally and got together with them. We've had it since then. And we have been, you know, in the process of community discovery, to look at what people in the area want to see. And, you know, there's been a range of things that have been raised by community residents. It depends on whether you're talking with somebody who lived very close to, and in that neighborhood, or somebody who lives in some other part of town.

We have had a number of community meetings to talk to people about what they want to do with the hospital building. And they haven't been conclusive. I've heard that people want something with very young children, with those who are not so young children, and then with teenagers, and with young adults to mature adults, and for senior citizens. You know, the basic thing is, people say, we want something that's gonna be useful. And all of these groups I just listed has needs. And no one has yet come forth very concretely, saying that they want to operate the facility for their own.

I would personally lean towards. you know, developing a close working relationship with somebody in that position and trying to make sure that they got the resources and support that they needed. But again, it has to be the group as a whole. It's matter of settling in on who is going to run it rather than what it will be used for.

AS: Why is that? I mean, I have some ideas as to why, but I'm curious.

EW: Why do I think the who is so important over the what?

AS: Yes, that’s what I mean.

EW: Because I know we can't do it. We won't. You know, the board of Delta Commons is only five people and we have other commitments. It's been almost two and a half years and we are still in this process of community discernment. You know, we have not been able to kind of move off of ground zero.

AS: I think part of it is a question of leadership and a question of community. In my experience people have lots of ideas. It's another thing when a community owns something and builds it themselves, right? I think that's different. It's a different process. It's harder. It's harder because people realize how difficult it it exactly is to run something, not just start it. I mean, people often just don't have the time. I think that's that's one of the challenges.

EW: And you know, if there is already an existing organization for which this would enhance their work, that would be one way to approach it. Other than that, you gotta take some time and build an organization. The challenge again is finding the people.

AS: What are the primary obstacles in developing people?

EW: What you just said, which is the people are already doing something. And so you have to develop some sort of agency. And then you have to help people manage the technical skills and tools. I always tell people, from the day you finish the rehab on a building, all buildings start to deteriorate. And so, unless you were setting something aside for what is going to be required to fix it when the roof starts leaking on it or the HVAC goes down, or some other problem — unless you're starting to accumulate that from the beginning, then you're just waiting for a crisis. And you know, it’s all prediction. Some of that is rooted in people’s social experience. You know, we have some sense of how long the roof will last. People should have those details and those capacities to actually operate.

I think a lot of people are seduced, by the idea that, you know, great riches can come from passive income. And I don't know life to work that way.

AS: Yeah, I mean, I think that's part of this challenge in community discernment. The social media culture feeds our society’s individuation, which, fits nicely with bootstrap capitalism: Just pull yourself up. But part of the the question that I’m interested in exploring here is how individualism fits with anti-institutionalism. It may the be the case that people can learn how to build an organization, but they don't want to, because people tend to not want to build organizations.

EW: I don’t know. All sorts of organizations or joint organizations exist. And, you know, people find meaningful roles for themselves all the time, whether it's church organization or whether it's the social club, or whether it's an informal social club that breaks the law, which people refer to as gangs. People join organizations. People build economic organizations around drug trafficking when they're not doing economic organization around real estate. You know, that's part of the human social character. We are social creatures. I don't necessarily think they do it in really what I call intentional ways all the time, right? People go to church because their parents went to church. Now, the social mores that kept people in church have also been damaged by the county’s short attention span, the Internet, and a get rich quick culture that's not connected with people thinking that somehow, you know, investing in long-term education and trying to find a secure job, and ultimately buying some real estate and hoping that it will appreciate.

AS: I so appreciate this attention to culture, because that was part of the the hope of the Delta and Providence farms. Sharecroppers and farmers got unjustly kicked off their their land in the bootheel of Missouri and Sherwood Eddy and other social gospelers raised money to buy the land. And they started a creative enterprise that they hoped could help them create an interracial, cooperative. It was always about embodying and living into an alternative culture, that had medical facilities, schools, job training. So, I think that’s partly why I'm curious about how prominent culture is in your thinking, because that was eventually its undoing at Delta and Providence farms. Both the white racism within it and and around it destroyed it, combined with the reality that the surrounding whites recognized that it was attacking plantation capitalism at its core. It's not just an issue of racial justice here. It was about building economic power.

EW: I’m interested in understanding the extent to which it was primarily racism or the interaction of racism with a lot of the prevailing attitudes at the time. Even among the black tenant farmers, I wonder to what extent their attitudes were closer to an individualism as opposed to collective security.

AS:Yes, talk more about that.

EW: So I mean, you know, it's easy, from one point of view to recognize their problems with racism. But to what extent did that prevent the black members of the group from proceeding to do what it was they needed to do, right? You know, farming is a productive activity, so it has to be contingent on an external supply of ongoing resources. You know, what you need is a fair price of product of your labor, and you need to take that fair price of the product of your labor, and very, very skillfully set portions aside, for you know, for land acquisition, for maintaining the infrastructure that's required to farm. We get all that. So, you know, I'm not sure that racism played a role in that. You know the number of folks that I've seen in situations where external rights haven't been the major factor. They succeed. They haven't always succeeded, you know. Yeah.

AS: Yeah. I mean, to me, this is pointing to the importance of what you were talking about earlier in terms of the Delta Commons. The way I hear it is: it’s the hard work of building a culture, of developing people who have the knowledge and skills to succeed. So you're holding all these community meetings, hearing what people want. But you're looking for the right people to step up and that can't just happen. There are outside factors that are making that difficult in the same way that it was making it difficult for the folk in 1930s and 1940s. You're going against this broader culture, which is real, and significant. I think that's also what's really interesting about this topic on cultural work, is how the work, then, of the Delta Commons is also grounded in investing in artists and cultural workers, right?

EW: Yeah, we talk a lot about that. And we try to support those activities when we can. You know, I personally have a lot of association with a lot of local artists, you know, I play a little, music, so I can get on stage with these guys and hang out with them or talk to them. I get invited to be part of bands. But, you know, there is a young musician I'm working with and I say to him, you know, if you get together with a group of musicians, I can help you all build some kind of musicians cooperative. We could probably get a venue, or or do some collective booking engagements.

He said in response: Why don't you help me doing it all by myself. I said, because I wanna work for the collective folks. But he responded again: So? If you invest in me personally, then I’m going to give back to the community. I said, that'd be nice. But, you know, that’s not what I’m about. So, I hear a lot of that, you know. I haven't figured out exactly what to do. Relationship building is a long-term game. And it takes a while and doesn’t always work out. Sometimes, you know, something will smash: some external event will give rise to people recognizing the need that they have to work with other people. But given the absence of that event, you know, folks have a lot of individualist ideology pushed on them. On a very consistent basis.

AS: That’s right and partly what I meant by anti-institutionalism. It’s the idea that I don't need to go and join others. Ed, thanks so much for this conversation. To end our conversation, what do you want readers to know about the Delta Commons?

EW: Just know that we're still in the process of trying to find our way and make sure that we're actually of benefit to community. And sometimes it’s a rewarding process, sure, but you know, all I can claim is that we're working at it.